18.10.24

Argomenti correlati

On the evening of April 5th, the sea off the coast of Sfax – Tunisia’s second largest city and a large port in the centre of the country – is calm and the air temperature is average. These are good weather conditions to attempt the crossing. Sfax is in fact the main starting point of the route from Tunisia to Lampedusa, one hundred kilometres further north.

The countryside surrounding the northern part of the city centre is the area that has seen the most departures of migrants of sub-Saharan origin in recent years. A shallow, smooth coast on one side, and stretches of olive groves in a sparsely populated area on the other, where migrants have set up several makeshift camps.

The investigation in a nutshell

- On April 5th 2024, a flimsy metal boat with 42 people on board from Gambia, Guinea and Sierra Leone sank off the coast of Sfax. These boats are very common along the coast, made by Tunisian mechanics who sell them at affordable prices

- The Tunisian Garde nationale is accused by the survivors of having caused the shipwreck, first by carrying out a series of deterrent manoeuvres, then by ramming the boat and hitting the migrants on board. At least 15 people died

- During 2023, several local and international civil society organisations accused the Tunisian authorities of carrying out violent operations at sea, causing shipwrecks and drownings

- For years, the EU and individual member states have been funding the Garde nationale. On 19th June 2024, Tunisia declared its own search and rescue zone with the support of Brussels. The EU has never taken an official stance on the violations along the Tunisian route

Off the coast

On the evening of April 5th, at least four separate groups, about 200 people in all, set off at different times in boats. These are very unstable, built with thin iron plates in repair shops by Tunisian mechanics specifically to allow migrants to leave. At La Louza, some 40 kilometres north of Sfax, there are dozens of them piled one on top of the other: a ship graveyard rusting away in the sun.

Three such boats eventually take to the sea. On the last one are 42 people from Gambia, Guinea and Sierra Leone. The boat is about eight metres long, with very narrow spaces, and there are pregnant women and eight minors on board. It leaves the coast of Sfax at around 7 pm hours local time. The sun has only just set but the light is already very dim.

Tear gas rains down on the passengers: Tunisian law enforcement are trying to prevent the migrants from leaving the coast. Some shots land in the water, others reach the boat, but someone from inside promptly tosses them overboard. The panic seems to be over, as the coastline becomes smaller and smaller with each passing minute.

After another brief stretch, the situation precipitates. Two black Garde nationale rubber boats, possibly donated by Germany as part of the migration cooperation between the two countries, according to some diplomatic sources, approach the migrants. One starts to draw circles in the water around their boat, three times, to produce waves.

It is a deterring technique to make navigation difficult, case deployed against an overloaded boat, with minimal buoyancy. Some of the migrants are crying, fearing they will be captured and taken back to Sfax; others stand up to show the children in the boat, begging the officers to call off the attack and let the boat go.

Their pleas are ignored.

The black dinghy engaged in the deterrent manoeuvre picks up speed and rams the stern of the boat. After the collision, a coastguard, armed with an iron bar, hits a few people and tries to seize the engines to prevent the boat from eventually going out to sea. This is repeated a total of five times and causes the migrants’ boat to break up; then the black dinghy pulls away.

Within minutes, the boat fills with water and sinks. This is how 21 men, 13 women and 8 minors find themselves in the open sea in no time at all. Most of them cannot swim.

The two Garde nationale dinghies are tens of metres away. The crew, two people in each boat, throw ropes to the migrants and film what is happening on their phones.

It is a tragic sight: some manage to reach the ropes, cling on and climb into the dinghies, which are too small to accommodate 42 people; those who cannot swim drown. After that, other boats from the Tunisian authorities join the black dinghies to help the migrants: two more white dinghies arrive, two medium-length boats and two 35-metre boats, donated by Italy in 2014.

Sostienici e partecipa a MyIrpi

The operations ended in the dead of the night, when the boats returned to the port of Sfax. The death toll is ghastly: at least 15 people have died in the shipwreck, including eight minors between the ages of 3 and 13. The fate of the survivors is sealed. They are all brought to the same pier, including the people on board the three other boats that left the same evening.

The hours pass, the sun rises again and the survivors’ skin begins to burn from the petrol that has stuck to their bodies and clothes. The migrants are lying or sitting, huddled, clinging to each other in a row.

This is also confirmed by a satellite photo taken by PlaceMarks: the same morning, after more violence, four buses load up most of the survivors and leave for the Libyan, where the migrants will be abandoned to their fate hours later. Only a few manage to leave the port of Sfax on their own two feet, avoiding deportation.

Captured at sea, left alone in the desert

Over the same weekend, the Garde nationale carried out several other operations and issued a statement a few days later via a Facebook video where dozens of people are seen entering the port of Sfax on board the 35-metre boat:

“As part of the fight against the phenomenon of irregular migration, over the weekend the Garde nationale managed to foil 85 illegal maritime border crossings, rescue and save 2,688 people (2,640 sub-Saharan Africans and 48 Tunisians) and recover 13 bodies.”

It is a widespread practice, sometimes even used strategically to document the Tunisian authorities’ ability to intervene.

It is a widespread practice, sometimes even used strategically to document the Tunisian authorities’ ability to intervene.

Survivors

We can know what happened on the night of April 5th thanks to those who survived the shipwreck. The various testimonies, collected at different times, agree on the details of the events, the means that the Garde nationale used at sea and on land, and the identification of the casualties through archive photos: seven minors, six women and two men. The identity of the casualties makes it impossible to reduce the incident to a “ghost shipwreck”.

While in the central Mediterranean route the presence of NGO ships has played a major role in witnessing the violent methods of the Libyan coast guard, in Tunisia there is an almost total lack of images or documentary evidence that can verify the causes of shipwrecks or incidents at sea. There are, however, the words of the survivors.

This context also helps to explain the discrepancies concerning the numbers of casualties. In the case of the April 5th shipwreck, for instance, the Garde nationale reports having recovered 13 bodies during rescue operations, while IrpiMedia was able to reconstruct the identity of 15 people. Survivors also claim there were 24 casualties in total.

These conflicting versions are often due to local authorities’ obstruction in the identification of the bodies. One survivor of the shipwreck reports that he asked some officials if he could take photos of the bodies to send them to the families in their countries of origin. The answer was a categorical ‘No’.

Reconstructing the April 5th shipwreck

- Individual face-to-face and telephone interviews with survivors to compare the different versions of the shipwreck

- Comparison of testimonies with videos shared on social networks about previous cases in which similar techniques were used

- Satellite image of the port of Sfax – taken by Placemarks – from 6 April. About 100 people can be seen sitting or lying on the pier in front of some Garde nationale vehicles

- Official statement from the Tunisian authorities saying that they had prevented several departures and recovered 13 bodies at sea

“I had never seen a boat hit another one deliberately. I had heard many stories about it but this is the first time I have it witnessed it with my own eyes.”

Several weeks have passed when Ibrahim (not his real name) recounts the details of the shipwreck. He would rather not disclose his identity, or even where he is based at the moment. However, one only has to look at his gaze as he talks about April 5th to feel the burden of grief he still carries with him today.

Born in Sierra Leone, as he recounts what happened that night he uses two mobile phones arranged on the ground, one in front of the other, to show the positions of the boats at sea

“Our boat broke down after being rammed by one of the two black rubber dinghies. When we had been in the water for about 30 minutes, the police realised that people were dying. At first they rescued six people, including me, and started to move us to other Garde nationale boats until we reached the port of Sfax.”

As Ibrahim tells the details of that night – from the tear gas to the beating at the hands of the coast guard, from the shipwreck to the arrival at the port of Sfax – seven-year-old boy is listening to him, completely captivated by his words. He is the only child who survived the 5 April massacre. He lost his mother that night:

“After the boat sank, I swam with him to the dinghy and we saved ourselves”, Ibrahim continues. “Afterwards I pretended to be his brother to protect him. Today, I cannot say that he is fully aware of what happened. Once I saw him crying, I asked him why but he could not give me an answer. He only said that maybe it was because his mother had died. It broke my heart”, he confides.

Kominata (not her real name) currently lives in a location she does not wish to disclose. Five months pregnant, she had left with her husband for Italy. During her retelling, she often pauses, struggling to get sentences out, and she often places her hands on her stomach for the pain she still feels after the physical trauma she suffered during the shipwreck:

“I was in the sea for nearly an hour before anyone helped me. When I managed to grab onto the rope, no one tugged at it to save me! Meanwhile people were drowning. I could no longer find my husband and most of the children died. Now I am alone and pregnant”, are all the words she manages to utter before she starts crying.

Ousman, from Gambia, was on one of the three other boats that were intercepted on the night of April 5th. His testimony is crucial for reconstructing what happened at the port of Sfax the following morning, because he was also able to collect photos and videos from the pier.

“People lay without clothes, food and water for the whole night”, he says. Then the police beat a Sudanese man until he bled. They had intercepted another boat before they got to ours, then two more and one of them sank. I know there were 13 dead, and that the police used tear gas at sea and beat people with iron bars”.

At 11:25 local time, Ousman sends a final voice note saying that he has to switch off his mobile phone because “[the police] are coming”. He then sends another message from the location of Nalut, a Libyan town in the desert, just over the border with Tunisia. At 10.58 pm, communications stopped, and there has been no contact since.

Thanks to the images sent in real time by Ousman, it was possible to locate exactly where and when the group of people was loaded onto buses and abandoned in Libya.

Suspicious shipwrecks: the data from NGOs

As the number of departures from Tunisia has increased in recent years, testimonies have also multiplied from those who claim they were intercepted at sea through violent methods that have led, directly or indirectly, to the death of migrants: tear gas, deliberate ramming and obstructions that have caused the flimsy metal boats to capsize, as they cannot withstand strong waves, especially when overloaded.

After the SAR zone was established on the eve of World Refugee Day, Alarm Phone, a NGO that provides support for people in distress crossing the Mediterranean Sea, has published Mare Interrotto, a collection of 14 testimonies from 2021 to 2023 recounting both the shipwrecks caused by the Garde nationale and the kind of illegal operations carried out at sea by Tunisian authorities.

On July 21st 2021, a dangerous manoeuvre led to the capsizing of the boat; there were 31 survivors, 29 people missing and 15 bodies found.

In other cases, there were reports of physical threats with firearms, use of tear gas, delays in rescue, deliberate ramming, engine theft and deportation into desert areas following capture at sea.

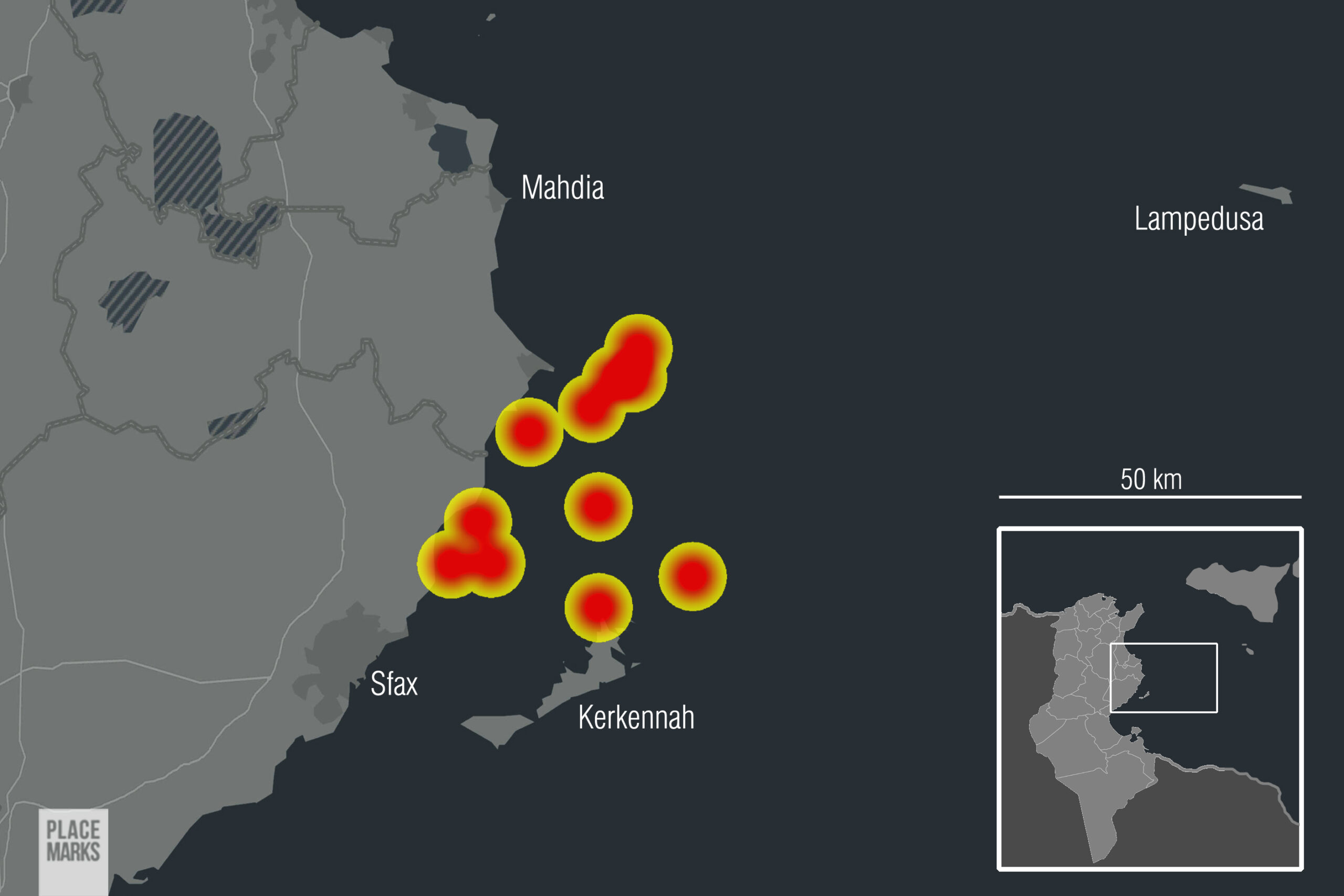

Stories closely resembling the shipwreck of April 5th were confirmed by videos circulating on social networks in 2023 and 2024. These operations nearly always take place in the same stretch of sea between Sfax and the Kerkennah archipelago, extending north to the city of Mahdia.

A Garde nationale vessel deliberately rams a metal boat with dozens of migrants on board.

According to the testimony of survivors, a similar technique was deployed in the shipwreck on April 5th.

Following a shipwreck, dozens of migrants try to board a Garde nationale patrol boat.

The video was made by a migrant on board a larger ship.

A Garde nationale vessel deliberately rams a metal boat with dozens of migrants on board.

According to the testimony of survivors, a similar technique was deployed in the shipwreck on April 5th.

Following a shipwreck, dozens of migrants try to board a Garde nationale patrol boat. The video was made by a migrant on board a larger ship.

A Garde nationale officer beats migrants with a wooden stick. Several testimonies report that Tunisian authorities routinely beat migrants with sticks and clubs.

Shipwrecks occur in coloured areas © PlaceMarks using data from Alarm Phone and IrpiMedia

According to data released by the Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights (FTDES), interceptions at sea have progressively increased in recent years: from 13,466 in 2020 to 48,805 in 2022, and 80,636 in 2023.

Over 1,300 migrants disappeared at sea in 2023 and 341 in June 2024. While these figures cannot be directly linked to the violent practices of the Tunisian Garde nationale, they do raise concerns about the possible increase in this type of violent operation.

On 19 June 2024, Tunisia officially communicated to the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) its search and rescue zone, an area that coastal countries declare to the UN agency in order to make recovery of people at sea more effective.

Although the Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre (MRCC) – which is in charge of operations – has existed since 2013, Tunis has never officially disclosed the extent of the area it would take charge of.

Now that the SAR zone officially exists, Tunisia can also leverage its European partners to increase the number of vessels that can intervene in a shipwreck, even those not involving migrants. The organisation of search and rescue operations is detailed in Decree Law 181 published in the Official Gazette, coincidentally, on April 5th 2024.

Tunisia and Libya: European funding for the Coast Guard

In Libya, the Coast Guard has a fragmented command structure over which the Ministry of Interior in Tripoli struggles to maintain control. In addition, there are several other maritime authorities linked to other ministries, and militias charged with intercepting migrants at sea.

In Tunisia, by contrast, the Garde nationale is the official corps of the gendarmerie responsible for security – on land and at sea – in rural and peri-urban areas, while the police is in charge of cities. An official state corps answering directly to the Ministry of the Interior, it was established in 1956, five months after the declaration of independence from France.

The Libyan Coast Guard has received substantial financial support from the European Commission since 2017, as 90 per cent of the 180,000 migrants who reached Italian shores in 2016 had departed from Libya. Eight years later, a similar model of border externalisation is being applied to Tunisia, the main departure point for migrants in 2023.

Accedi alla community di lettori MyIrpi

One year since the signing of the Memorandum of Understanding between Tunisia and the European Commission, it is possible to reconstruct the destination of the 105 million euro pledged by the EU:

17 million were allocated to the implementation of the SAR zone and the supply of new vessels; 13 million were allocated to the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), and eight to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to ensure the protection of migrants on Tunisian soil; 18 million to the United Nations Office for Drug Control and Crime Prevention (UNODC); another 18 were distributed for the supply of additional naval assets with the support of UNOPS, the United Nations Office for Services and Projects, Finally, 30 euro million were assigned to the International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD), an international agency with expertise in supplying equipment to third countries.

In addition to the Commission’s funds, there are those from individual member states. The black rubber boats used by the Garde nationale on the night of April 5th, for instance, may have been supplied by Germany, according to information from various diplomatic sources.

Mandatory surveillance and radar equipment for navigation at sea, which the survivors recognised on the night of the shipwreck, are the result of the Border management programme for the Maghreb Region (BMP-Maghreb), implemented by ICMPD.

The EUR 105 million provided by the memorandum come in addition to previous funds and supplies.

The BMP – Maghreb programme, for instance, also provided surveillance and radar equipment to naval units. White dinghies equipped with such technology were recognised by survivors of the April 5th shipwreck. This equipment can also be seen in some of the videos where the Tunisian Garde nationale is carrying out violent operations.

The authorities in Tunis did not respond to requests for an official statement on the April incident and the other allegations reported by various witnesses and international organisations.

king place in Tunisian waters. In response to our questions, a spokesperson replied: “The Commission monitors its programmes through several means, including regular reports from implementing partners, external evaluation, verification missions and results-oriented monitoring. EU funded capacity building for the Tunisian authorities, including equipment and training are provided solely for the purposes defined in the EU funded programmes, with full respect to international law. ”

Ibrahim, one of the witnesses who lived through the 5 April shipwreck, sees it differently: “If you are not saving people, at least don’t destroy their lives. I lost my sister, my nephews and my brother’s wife.”

Read also

Thanks to European supplies, Tunisia has gained more and more intervention capabilities over the years. Despite the training of Tunisian officers, however, there are fears that this will lead to an increase in abuse and violence against sub-Saharan migrants attempting to cross the sea.

This was partially confirmed by the Council of State in Rome, which on June 20th 2024 suspended the supply of six Guardia di Finanza patrol boats, to be repaired and delivered to Tunisia according to a Ministry of the Interior decision signed in December 2023, for a total value of 4.8 million euro.

By accepting a complaint filed by Asgi, Arci, ActionAid, Mediterranea Saving Humans, Spazi Circolari and Le Carbet, the Council of State acknowledged their concerns over possible human rights violations at the hands of the Garde nationale:

“As the United Nations has also argued, providing patrol boats to the Tunisian authorities means increasing the risk of migrants being subjected to illegal deportations”, said Maria Teresa Brocchetto, Luce Bonzano and Cristina Laura Cecchini from the pool of lawyers who are working on the case.

However, on July 4th 2024, the Third Section of the Council of State overruled the decision, upholding the legitimacy of the supply, recognising the relations between Italy and Tunisia, and confirming that the latter was included on the list of safe countries by the authorities in Rome.

In the absence of a clear stance from European and Italian institutions, the temporary suspension of the six patrol boats marks an important precedent in recognising the violent operations carried out by the Garde nationale.

Le inchieste e gli eventi di IrpiMedia sono anche su WhatsApp. Clicca qui per iscriverti e restare sempre aggiornat*. Ricordati di scegliere “Iscriviti” e di attivare le notifiche.